Good day everyone—a new roundup of commentary for you.

As always, for consistent (near-daily) culture updates, check out the blog at The Bridgehead. There’s a column on a win for religious liberty in the UK; one on why Boris Johnson’s decision not to include transgenderism in his “conversion therapy ban” is so important; a summary of the reaction of abortion activists to the possible overthrow of Roe (which includes firebombing a pro-life office); and an explainer on why the Twitter account Libs of TikTok is so effective at exposing what LGBT activists are teaching to children.

On the podcast, Dr. Michael New—one of the premier scholars on abortion in America—explains what a post-Roe America might look like.

At The European Conservative, I have an essay on the rise of Dr. Leslyn Lewis, a populist candidate in Canada who is shaking up the Conservative Party.

Finally, here’s my latest essay, which can also be found at First Things under the title “How Mary Whitehouse waged war on pornography”:

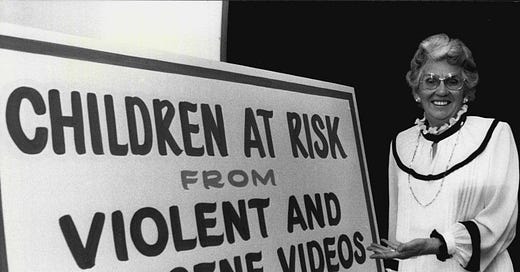

Mary Whitehouse was right about everything

We have reached the point where our post-Christian elites, having safely enshrined the sexual revolution in law, can afford the luxury of occasionally admitting that their opponents were right. Exhibit A is the new BBC documentary Banned! The Mary Whitehouse Story, which details the life of Great Britain’s most infamous morality campaigner. Beginning with a crusade to keep smut and blasphemy off TV in 1964, Whitehouse rallied hundreds of thousands of women (and ordinary Britons) to her campaigns against “the permissive society,” culminating in her war against the porn industry. Alas, she lost most of her battles—but her warnings proved prophetic.

Mary Whitehouse was born in Warwickshire in 1910. She first started organizing in the 1960s because she—and millions of other mothers—did not like what her children were seeing on TV. A committed traditional Christian, she watched with dismay as the country she loved began to change around her. The metropolitan elites she faced off with thought she was “a provincial Birmingham housewife.” They didn’t underestimate her for long. She hosted her first mass meeting in 1964, and her organizing skills soon highlighted the subterranean power of Britain’s women. Whitehouse tapped into the gardening associations, the mothers’ unions, and other grassroots community organizations filled with folks who cared deeply about their children and the moral fabric of their nation. She brought them together, and when she spoke, it was with the voices of legions of little people. Her nickname summed it up: “The avenging angel of Middle England.”

Whitehouse’s first major campaign was to “Clean Up TV,” and her parliamentary petition to that end garnered around 500,000 signatures. In 1971, Whitehouse began organizing against sex ed in schools, triggered by an “educational” video she saw that was filled with pornographic scenes. Whitehouse was accused of hysteria—but Banned! features a pornographer admitting that, by using sex ed, “we gradually pushed back the barriers,” much as Whitehouse warned they would. Now that they’ve won, they can admit they were lying.

Whitehouse and others appalled by attempts to corrupt their children were accused of being “horrified by sex.” In reality, they were horrified by the version of sex presented by sex educators—in much the same way an art lover would be appalled to see vandals approaching a great masterpiece with cans of spray-paint and lewd laughter. Progressives never understood this, and consequently Whitehouse has been almost entirely defined by what she fought against rather than what she fought for.

Whitehouse’s lobbying resulted in several pieces of legislation, including the 1981 Indecent Displays Act, which sought to restrain sex shops and the display of porn, as well as the 1984 Video Recordings Act, intended to limit the sale of extreme video content. Unfortunately, these acts were rendered moot by the internet. But her greatest achievement was the 1978 Protection of Children Act, which criminalized child pornography. It seems remarkable that such a law did not already exist, but in the ’70s the Paedophile Information Exchange (PIE) was operating openly in Britain; it was supported by some British elites who believed that sex with children was the natural next step in sexual liberation.

Whitehouse was mercilessly mocked for warning about the sexualization of children, but PIE was actually campaigning for “children’s sexuality,” advocating the elimination or reduction of the age of consent, and advertising legal help for pedophiles who got caught. The prominent Campaign for Homosexual Equality passed motions in favor of PIE at their conferences—twice. A major British newspaper told the story of one vote with the headline, “Child-lovers win fight for role in Gay Lib.” Representatives from PIE defended sex with children on the BBC, claiming that underage boys and girls could give consent to adults. When one president of the Young Liberals condemned pedophilia as “a wholly undesirable abnormality,” another colleague condemned him: “It is sad that Peter has joined the hang ‘em and flog ‘em brigade. His views are not the views of most Young Liberals.” On the question of the sexual abuse of children, Whitehouse and her supporters got it right—and many progressives got it wrong. That should never, ever be forgotten.

The misogyny leveled at Whitehouse for her condemnations of the permissive society was revealing. It wasn’t just the BBC-funded play dedicated to mocking her (virtue is more easily scorned than practiced); a host burning her 1967 book Cleaning Up TV on the free-speech loving BBC; the death threats and the physical assaults. Sir Hugh Greene, director general of the BBC from 1960 to 1969, hated Whitehouse so much he purchased a portrait of her by James Isherwood that depicted her naked with five breasts. Greene told the newspapers that he bought the hideous portrait as a dartboard, and reportedly crowed with pleasure whenever he hit one of the breasts.

Pornographer David Sullivan attacked her by launching a porn magazine called Whitehouse, which featured a prostitute named Mary Whitehouse who traveled about the U.K. and slept around (she eventually committed suicide). The point of all this, from Greene’s dart-throwing to Sullivan’s perverse magazine, was not simply to oppose Whitehouse, but to degrade her with a public sexual humiliation. In the name of sexual liberation and progress, Whitehouse’s male critics—and they were nearly all male—produced an early form of revenge porn. Britain’s elites chortled about it. Their views on egalitarianism didn’t extend to pesky defenders of Christian values.

Whitehouse was most prophetic on the poisonous effects of widespread pornography, which she called “the dirty face of capitalism.” She described getting letters from scores of women with porn-addicted partners who wanted to try out what they had seen in porn. A pornified society, she declared, made women suffer. Indeed, a 2021 Ofsted report revealed that 80 percent of girls are now pressured to provide sexual images; a recent essay in The Atlantic noted that 24 percent of adult American women feel fear during intimacy due to porn-inspired choking; police in the U.K. are warning that a generation of young men brought up on digital porn are becoming “online paedophiles.” Even The Guardian, Whitehouse’s old nemesis, recently admitted that porn-viewing has become normal for children.

Whitehouse warned that the spread of pornography would result in sexual violence. Perhaps not even she could have predicted what has actually come to pass: The acceptance of sexual violence in the romantic context. One major newspaper recently noted that a man had been accused of “unwanted sexual violence.” An entire revolution is contained within the word “unwanted”—and an untold amount of tears and suffering, too.

Whitehouse was mocked for predicting that sexual messaging would soon target children; it is now the norm for LGBT content to appear on children’s TV shows and in storybooks. She warned that films such as Bernardo Bertolucci’s Last Tango in Paris crossed a line; it was later revealed that the rape scene in the movie deeply traumatized the scene's young actress, who received vile treatment at the hands of older men. On the big cultural questions, Whitehouse was right and her critics were wrong.

For those who embrace our new pornified world, liberated from self-sacrificial love and responsibility, Mary Whitehouse was a villain. It is easy to criticize her infelicities, her blunt language. But when she warned that the porn industry would lead to “the degradation of the whole culture,” was she not correct? Despite the hearty chuckles from her opponents then and the BBC documentarians now, was there not a “conspiracy to corrupt public morals”—one that succeeded beyond the wildest imaginings of the most fervent sexual revolutionaries?

There was. Mary Whitehouse was not simply a moralizing paranoiac, and at some point a half-century ago, we faced a choice. Would we live in the vanishing society championed by Whitehouse? Or would we inhabit a new one, shaped by the vile fantasies of the pornographers? The choice was made, and we are all living with it.