“Ukraine is Not Russia”: What I Saw on the Ground

Note: This is my report from Ukraine published in the fall print edition of The European Conservative, which has just been put online. My two previous reports were published in TEC (on Ukraine and conspiracy theories) and First Things (on how religious communities are dealing with the war). I’ll have another newsletter with some new columns on culture war issues out shortly. Thanks for reading!

My colleague and I arrived in Ukraine six months after the Russian invasion began, crossing the border from Hungary and meeting our driver in Uzhhorod to head for Lviv. The scenery is so beautiful it is almost kitschy: endless fields of wheat and sunflowers, little wooden cathedrals, trees sagging with fruit, mountainous woodpiles, enormous traditional haystacks, and harvesters with scythes hard at work in the fields all interrupted by the occasional Soviet statue.

In the countryside surrounding the Carpathians, history seems to sleep lightly. Indeed, the graveyards are topsy-turvy with tall crosses of metal and stone, where, for generations, war has sown her rotten seeds. In Kyiv and in the east, fresh youths have been planted in orderly cemetery rows to await the spring of Resurrection.

Lviv is full of soldiers: a father walking with his teenage daughter; a young couple embracing; giggling girls approaching clusters of uniforms. Nearly every billboard has been requisitioned for patriotic propaganda, and in the large square near Old Town, the Ukrainian Defence Ministry has set up an exhibition of smashed-up rusty Russian weaponry and descriptions of the captured booty. Teens take selfies; children hang off the guns; young men have their photos taken, flexing in front of shattered tanks. “We shall overcome. We shall triumph,” the Defence Ministry’s signs say.

Displays of this sort are a key part of Ukrainian morale boosting. I saw several in Kyiv, including a graveyard of Russian military vehicles dumped on the cobblestones in front of the thousand-year-old St. Sophia Cathedral. We saw many tanks and armoured vehicles destroyed during the Battle of Kyiv (which lasted until the Russian withdrawal in early April) simply pushed off the road and left there. One Lviv poster featuring a sketch of a muscular Volodymyr Zelensky and other military leaders summed up the attitude: “Ukrainian Fight Club: Fights Will Go On As Long As They Have to.”

Other than the posters, occasional anti-tank barriers (which grew thicker on the ground the closer we got to Kyiv), and the sandbagged windows and doors of bomb shelters, Lviv could be any other European city. There’s a lot of smoking, traffic, and bad hair dye; beautiful children play in the coloured fountain spouting streams of incandescent blue, green, and yellow in front of the Opera House. The young people are all glued to their smartphones—if Russian rockets hit, legions of them wouldn’t notice until impact. Little kiosks have popped up everywhere selling flags, toilet paper with Putin’s face on each square, and signs featuring a coffee cup with a pistol next to it: “Good morning. First we eat breakfast, then we kill Russians.

The countryside surrounding Kyiv is peaceful but war-haunted. Intersections bristle with anti-tank barricades; some are sandbagged; others have logs wrapped in barbed wire at the ready. Makeshift camouflaged bunkers are everywhere, with the netting sewn from thousands of scraps of dresses, pants, underwear, nylons—whatever people could find. When we reach the outskirts, we find large stretches of highway newly repaved. Many of the road signs still have their names blacked out with paint to deter the invaders. Scores of buildings are badly damaged from rocket fire. It is surreal to consider how close the Russians got to the capital.

War is the backdrop in Kyiv. There is a strictly-enforced curfew at 11 p.m.—even restaurants and bars begin to close much earlier. Uniformed soldiers mingle with joggers and shoppers and people getting coffee at kiosks on the way to work. Well-dressed young women clip-clop past rusty anti-tank barriers and barbed wire. A young father hoists his daughter onto his shoulders. She giggles. It’s grotesque to consider what bombs and shrapnel do to such scenes.

We headed to Hostomel Airport, guided by a local doctor, Vitalii Solomenko. The Russian Airborne Forces landed here on February 24 intending to secure a key transportation objective for a further assault on Kyiv. After initially being repelled by Ukrainian forces, they retook and held the airport until the end of March. The surrounding area took a pounding. All the windows were blown out in the nearby school. A cleanup crew of children entered it as we passed by. Across the road, many of the civilian apartment blocks had their sides peeled away as if by a giant hand, with the insides spilling out onto the grass. The apartment in which Vitalii’s uncle lived was one of them.

Many buildings took direct hits and were charred and skeletal, with girders thrusting out at crazy angles like broken bones. Alexandra, an old woman without any teeth, showed us the jagged hole where her apartment had been. She beamed at us as we talked through a translator. The Ukrainians we met have a dogged determination to go on—despite the destruction, people chatted and laughed with one another; several were weed-eating along the curbs in front of the broken apartment blocks. The challenge of rebuilding looks insurmountable, but the work is underway, nonetheless. Spray-painted on the side of one of the buildings: “We want to live here!”

We visited Irpin, Borodyanka, and Makariv. Everywhere we went, apartment buildings and homes had been gutted. Some apartments are in pristine condition, while the buildings just next door are crushed. War is a weird surgeon. The local scenery is surreal: backyard fences spattered with bullet and shrapnel holes, a woman sweeping the front walk of her half-smashed house, a man outside a ground-floor apartment with shattered windows repainting his bannisters. A young blond woman was striding into the rubble-strewn courtyard of an apartment complex with a fresh coffee and toting a paper bag of school supplies for impoverished children. The front of her t-shirt read, in bold letters: “Best. Day. Ever.”

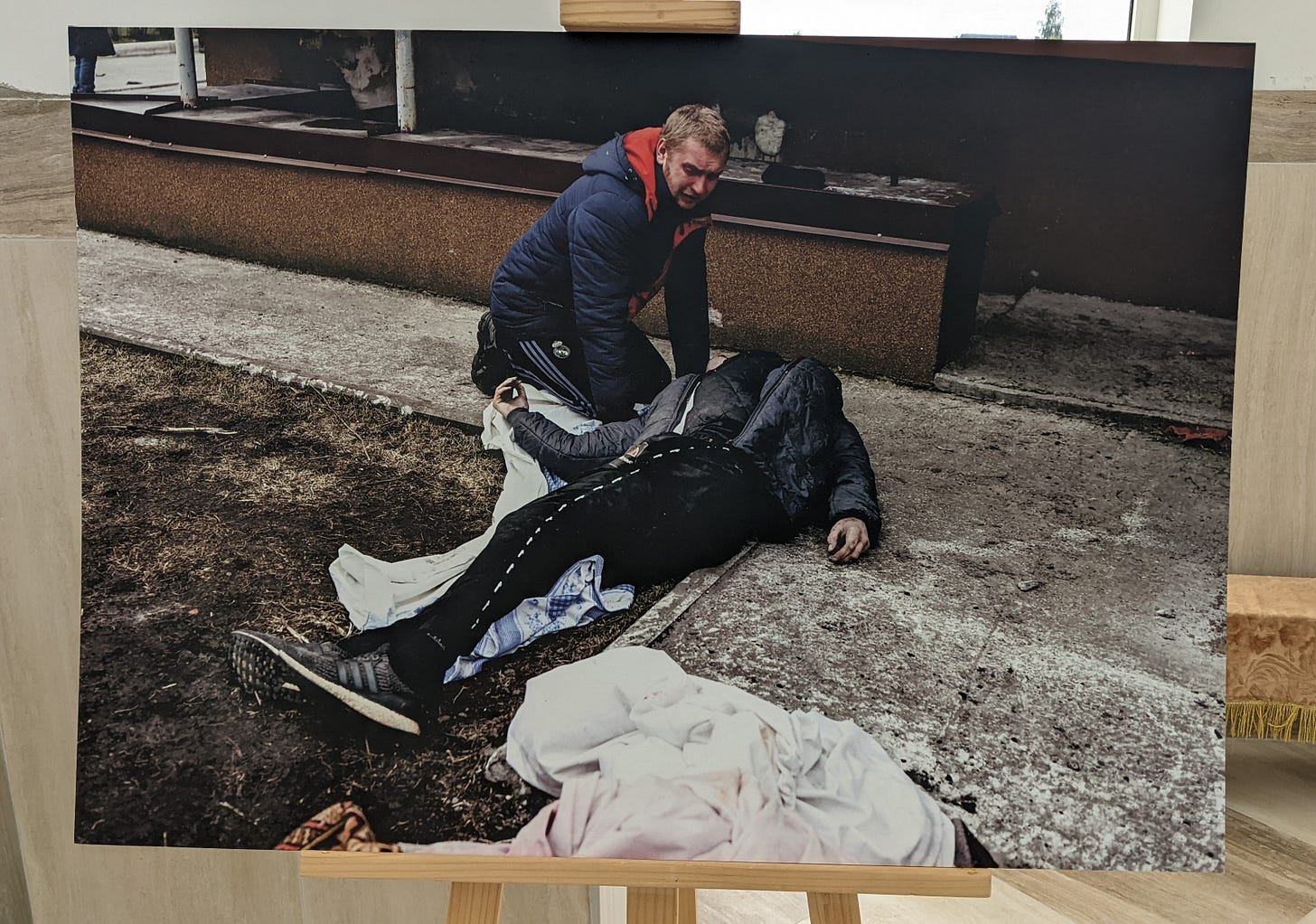

An elderly woman in a red shawl unlocks the church door for us in Bucha. After the Russian withdrawal, a mass grave was found on the church grounds, and in the sanctuary a display of photos is set up on easels. One depicts a cluster of grief-stricken townspeople looking at a row of corpses covered in black plastic. A young man, his face contorted with grief, bent over the body of an older man sprawled on the sidewalk; a body flung from a blue bike onto the sidewalk; a dog waiting patiently beside a corpse for his owner to wake up. One showed a body with arms tied behind his back. Outside, a metal cross and a pile of flowers and teddy bears marks the spot where the victims were buried before being exhumed and reinterred in the local cemetery. Our driver lit a candle, cupped it against the wind, and planted it among the remembrances.

It is clear that war crimes have taken place in Ukraine—more than 300 dead civilians were found in Bucha after the Russian retreat. The Russians have also indiscriminately bombed civilian areas. But is it genocide, as is claimed by President Zelensky (and many of those we interviewed)? That is more difficult to discern. I asked a soldier in Bucha if the civilians buried in the mass grave outside the church had been executed systematically (as the photo of the man with the bound arms would seem to indicate) or killed in the chaos of the fighting. He shook his head. “Scared sh*tless Chechens shot at everything that moved and killed a ton of people,” he replied. (It bears mentioning that the Chechen soldiers have earned a reputation for brutality.)

I asked if there were other atrocities, of the sort documented both by the Ukrainians and the foreign press in other areas. “There was a video going around of a Russian doing f****d up sh*t to a baby with a knife,” he said. “But we don’t know if it was real.” Several young girls have reported being raped by the Russian occupiers, and autopsies of women who were shot confirm that they were sexually assaulted. Investigators have also reported finding mutilated corpses—one of those recovered from the mass grave in Bucha had been beheaded. (On September 23, a report released by independent international investigators confirmed a wide range of war crimes.) “They’ve behaved like animals the whole war,” the soldier told me, before asking “and why are they shooting civilians?”

There was similar uncertainty in nearby Chernihiv, where we toured the hospital. A doctor and medical director took us to the cardiology building, which had taken a direct hit from a Russian rocket along with several nearby apartments and the Hotel Ukraine. The main hospital is back to full function after the chaotic days of the invasion and occupation, but the cardiology building is still a wreck. This, the director told us, was evidence of genocide. I asked if the hospital had been intentionally targeted. “I don’t know,” he said with a shrug.

A young female doctor named Katya showed us around Chernihiv and recounted their losses. Their hospital was flooded with casualties immediately following the invasion. More than 1,000 people were treated during active hostilities—some soldiers, mostly civilians. Twenty-four operating rooms operated 24-hours-a-day, with surgeries being combined to accommodate the number of people arriving. When the water and electricity were cut off, medical equipment became unusable. People began to arrive with diarrhea from the lack of sanitation, and pneumonia and other diseases due to the cold. The camaraderie among the medical staff, forged on the frontlines of an ongoing war, was palpable.

Everyone here has suffered. Katya’s mother and younger sister took refuge in the Netherlands, but her father, grandmother, and boyfriend remained behind. “My aunt and my fourteen-year-old cousin were killed when a bomb hit their house,” she told us.

The Russians occupied the region surrounding Chernihiv for six weeks; one of the doctors told us that his family lived under the occupation. “Russian soldiers patrolled all the time, and everyone was so scared,” he reported. I asked Katya if any civilians had been killed by Russian soldiers—she knew of only one example. The Russians asked a local forester for the names of those who owned guns, and when he would not (or perhaps could not) give the information, he was shot. The Russians retreated from the area on April 5. Rebuilding has begun here, too—the bridges destroyed by Ukrainian forces are now swarming with construction crews, once again connecting the oblast to the capital region.

Irrespective of whether Russian war crimes in Ukraine constitute genocide (or “acts of genocide,” as some leaders have more carefully put it), it is easy to understand why so many Ukrainians default to the term, as almost every interviewee did at some point. Primarily, there is the fact that the Russian military has intentionally bombarded civilian areas (with many of the bombed or shelled towns and small cities not even being remotely close to any potential military target). But “cultural genocide”—defined as “the systematic destruction of traditions, values, language, and other elements that make one group distinct from one another”—does capture, for many Ukrainians, what Putin is attempting to do. Time and again, we heard one phrase, repeated with urgency: “Ukraine is not Russia!”

One popular military poster, featuring the massive bust of Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko bowing towards still-smoking apartment buildings in Borodyanka—we saw the scene during our visit there—sums it up succinctly with a single slogan: “Battle For Identity.”

In a world filled with people claiming to fight for freedom, the Ukrainians are truly doing it, and at great personal cost. Before we left Kyiv, I wandered through the Maidan Square. On a green lawn near the Independence Monument is a sea of little Ukrainian flags. On each flag, written in black marker, is the name of someone who has been killed since the Russian invasion. As I watched, people came up to plant new flags: a mother with two little girls; a soldier crouching in front of the curb to write a name on a flag. Others slowly made their way past, squinting to read the names. A black sign contained a row of numbers, which had been updated: “Ukrainians Killed By Putin: 4,436. 7,436. 10,789.” Russian casualties have proven impossible to determine, with some estimates running as high as 50,000. These are 20th-century corpse counts in a 21st-century war.

It is a red war in Europe, and ideologues of every stripe are uncomfortable—the Left, because of their distrust of the muscular nationalism driving the Ukrainians; the Right, due to distrust of the Left’s embrace of the Ukrainian cause and fear of an expansion of the conflict after decades of ‘forever wars’ in the Middle East. But beyond all that, there is something profoundly inspiring about what the Ukrainians are doing in defending their homes and homeland, their heritage and their people. The international politics of this conflict are messy and complex, and I do not pretend to understand them all. But from a nationalist—indeed, from a merely human—perspective, it is impossible not to admire Ukrainians for their courage, their tenacity, and their very survival. “Ukraine is not Russia,” they told us, over and over again. Perhaps it really is as simple as that.