Happy New Year, everyone!

I didn’t want to send out any newsletters over the holidays, but I did have a couple of essays published over at The European Conservative (where I’m a contributing editor) that some of you might find interesting:

When Middle Earth Came to Vienna

The Forgotten Christmas Story by Charles Dickens

I have several more coming out in TEC and First Things over the next month, as well—as well as some big podcast news coming up shortly.

For those interested in the pro-life work of the Canadian Centre for Bio-Ethical Reform (where I serve as communications director), give this a listen—there’s a lot more good news than you might suspect. As always, I post short culture updates consistently over at The Bridgehead.

Today’s essay is on a grim subject, but one I think we’ll be hearing a lot more about in 2023.

Where assisted suicide, despair, and the transgender movement meet

Just hours before she died on September 30, 2013, forty-four-year-old “Nathan” Verhelst—a woman formerly named Nancy who had been attempting to transition to male for years—explained why she had requested euthanasia. After beginning hormone therapy in 2009, she had undergone a double mastectomy and then an operation to create a penis. But when she saw herself post-surgery, she was filled with despair. “I was ready to celebrate my new birth,” she told a Belgian news outlet. “But when I looked in the mirror, I was disgusted with myself.”

Belgium permits euthanasia for “constant and unbearable physical or psychological pain” stemming from an “accident or incurable illness,” and Verhelst’s condition qualified. “My new breasts did not match my expectations and my new penis had symptoms of rejection,” she said sadly. “I do not want to be…a monster.” Instead, she took her suffering to a doctor. She was killed by lethal injection.

That was nearly a decade ago, before the transgender movement had conquered the culture and before the surge of youth identifying as transgender and the legions of young people going on hormone therapy and opting for sex change surgeries. It was also before the trend of “detransitioners” arrived—first in a trickle and now, it seems, a wave. What struck me about Verhelst’s regret and disgust is how similar her words are to the testimonies of many detransitioners who are now going public and testifying about how the transgender industry destroyed their bodies and the despair and self-loathing many of them feel as a result.

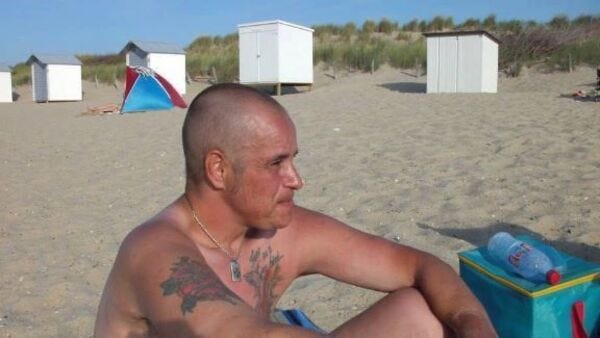

I recalled the awful story of Nancy Verhelst when I came across a similar story in a documentary recently released by BNNVARA, a TV network associated with the Dutch public broadcaster. It featured the story of Patrick, who for some time identified as a woman, but became unhappy with his transition. He decided to cut his hair and go back to living as a man. “But that didn’t make me happy,” he related. “I can never be myself again.” He was—as so many are—irreversibly impacted by the transition. “My belly and my bladder are constantly bugging me,” he said. He summarized his life in a single word: “Pain.”

And so, the documentary related: “After years of therapy, Patrick qualified for endless unbearable suffering. He has permission for euthanasia and his psychiatrist Gert Bakker wants to help him.” Patrick sobbed to the camera: “If I want to end my life, Gert will help me. But it’s a huge step and also irreversible.” The video clip was posted to Twitter under the title “Detransitioner euthanized after sex change surgery fail.”

As more detransitioners come forward, we may see more Patricks. Tens of thousand of young people are being physically ruined and turned into lifelong medical patients by the transgender industry. Detransitioners like Chloe Cole have stated that we are about to see thousands more coming out to publicly express their regret as they realize what has been done to them. And then—what of those who become suicidal as they face a life marked by irreversible damage, infertility, and in many cases, an inability to experience sexual intimacy? Trans activists constantly bombard us with deceitful emotional blackmail, claiming that refusing hormone therapy and sex change surgeries to minors will cause suicides. But what of the detransitioners?

As I noted in my 2016 book The Culture War, we are seeing each of our social ills intersect and interlock to create a hellish existence for those struggling to make their way in this broken civilization. The mainstreaming of sexual violence by pornography, for example, is spurring some young girls to identify as males simply because they look at the sadism built into our metastasizing sexual landscape and decide that they would prefer rejecting femininity to participation. The breakdown of the family is creating atomized young people desperate for a tribe to identify with—something that the transgender movement has been able to exploit brilliantly, especially as identifying as LGBT is presented as a way of becoming inherently worth of love and affirmation. And now, we see that the final step to radical autonomy—the right not only to define yourself however you like, but to freely choose self-extinction—has arrived just in time to provide an exit for those who have been mulched in the meatgrinder of the sexual revolution and do not have the strength to go on.

In his recent New York Times column on Canada’s suicide regime, Ross Douthat observed that we are beginning to “see the dark ways euthanasia interacts with other late-modern problems – the isolation imposed by family breakdown, the spread of chronic illness and depression, the pressure on aging, low-birthrate societies to cut their healthcare costs.” The freedom to commit suicide with assistance, he observes, is no freedom at all, and embracing this idea “will forge a cruel, brave new world, a dehumanizing final chapter for the liberal story.” The intersectionality of the sexual revolution shows us how sex changes, violent pornography, and broken families hideously mesh together. I suspect that we are about to discover the role assisted suicide will play in this sick story as it continues to unfold.

This madness is becoming a matter of life and death.